EMDR Therapy in Madrid: What it is and How it can help you

Have you ever felt like a painful memory continues to haunt you as if it just happened yesterday? An accident, an unexpected loss, abuse, a difficult breakup, or even a childhood marked by constant demands and criticism can shape the way we think, feel, and relate to others today.

Even though you try to «move on,» you notice that in certain situations, your body and mind react as if you were reliving it over and over again, making you feel trapped in the past.

There are life experiences that leave such a profound mark that they seem to be etched in the body and mind. EMDR therapy is an innovative and scientifically proven psychological approach that helps reprocess these painful experiences so that they no longer have the power to block us. In my clinical practice in Madrid (both in person and online), I have seen patients of very different ages and cultures surprised by the speed and depth in which EMDR transforms their relationship with the past and present.

What is EMDR therapy?

EMDR stands for Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing. It was created in the late 1980s by psychologist Francine Shapiro, who discovered that eye movements could help process traumatic memories in a more adaptive way.

In EMDR, the therapist first analyzes how the patient’s history is impacting their present. Then in the intervention phase, the patient fixes their gaze on their therapist’s fingers as they move side to side (leading the eyes to move repeatedly back and forth) while they think about and discuss the memory or experience that is being worked on. In some interventions alternative methods may be used to stimulate the brain such as tapping, a butterfly hug, or bilateral sounds.

Simply put, EMDR therapy doesn’t erase memories, but rather helps integrate them. The person still remembers what happened, but the memory is no longer burdened with intense and disturbing emotions. The past stays in the past, and the present becomes habitable again.

Today, the World Health Organization (WHO), the American Psychological Association (APA), and the Spanish Ministry of Health recommend EMDR as one of the most effective treatments for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

What is EMDR used for?

Although EMDR was originally developed for the treatment of PTSD, we now know that it is effective for a wide variety of emotional and psychological difficulties.

Trauma and post-traumatic stress

EMDR is a highly recommended treatment for people who’ve been through extreme experiences, such as war correspondents in dangerous locations or US military personnel who developed PTSD after their missions. Thanks to EMDR, they are able to reprocess memories that had previously paralyzed them: explosions, scenes of violence, and the constant feeling of danger, among many others. After a few EMDR sessions, one patient was able to sleep through the night again after many restless years, and his nightmares disappeared.

Abuse and family trauma

In both cases of child and adult sexual abuse, as well as in abusive relationships, EMDR has proven to be a transformative tool. I also use it with people who grew up under excessive pressure from their parents, which generated emotional trauma linked to impossible expectations.

I have been able to treat several people who had developed a tendency to feel anger or anxiety due to expectations placed on them by their families, leading to emotional disconnection and communication problems. After a few EMDR sessions, they were able to rediscover themselves as much more patient and tolerant people, and this helped them develop new communication skills and improve their marriage or familial relationships.

Anxiety and phobias

EMDR is also useful for those suffering from generalized anxiety, social phobia, or specific fears. Patients with social phobia, for example, often discover that their fear of public speaking was linked to memories of being teased at school and the wound it left. By reprocessing these memories, patients with these symptoms can free themselves from the anxiety that prevents them from developing in life, getting to the root of beliefs such as «I’m not good enough,» «I’m weird,» or «I’m hopeless,» among many others.

Grief and life blocks

When grief becomes «stuck,» EMDR facilitates the integration of the loss. It has also been successfully applied to self-esteem issues, blocks related to sexual identity, or even difficulties with weight control, when underlying traumas linked to food, the body, or the critical view of one’s family are at work. In short, it is a very useful tool for addressing negative beliefs about oneself that manifest in an inability to live happily even though, in theory, our needs are perfectly met. With EMDR, we can help change ways of thinking about ourselves, others, or the world that make it difficult for us to be happy.

How do you know if EMDR is for you?

EMDR therapy could be a good option for you if you identify with one or more of the following situations:

- You have memories that appear intrusively and painfully, such as flashbacks or nightmares.

- You avoid places, people, or situations that remind you of the past.

- You feel stuck in some aspect of your life and can’t move forward, even though you try.

- Your body reacts with anxiety, tension, or nervousness even though you know that there is no threat.

- You have a constant feeling of alertness or feeling that something bad may happen.

- You think you don’t have the ability or worth to do things (low self-esteem).

How does a session of EMDR work?

EMDR therapy follows a structured eight-phase protocol that assures the security of both the therapist and the patient. In my experience, this clarity of the process is one of the reasons that EMDR is so effective: it allows you to go step by step to find the root of the problem without the path being chaotic or overwhelming.

Before going in depth about the specific phases, I would like to first address some common questions and misconceptions:

“Am I going to be hypnotized?”

✖ No. In EMDR sessions, you will be completely aware of everything and in control of the process the whole time.

“Am I going to forget what happened to me?”

✖ No. The memory will remain, but the pain and impact of it on your daily life will stop.

“Is it only useful for serious traumas?”

✖ No. In many cases, it is the accumulation of negative experiences from your upbringing that cause different symptoms such as anxiety, discomfort with oneself, etc. It is also very helpful with phobias, breakups, grief, or low self-esteem.

“The process is too intense and I won’t be able to handle it.”

✖No. The process is gradual and before starting the reprocessing, you practice emotional regulation strategies that will help you feel safe and confident in the process.

The treatment phases

- History and Treatment Planning: We discuss the patient’s history and discover what traumas we will work on reprocessing

- Preparation: We explain the EMDR process to the patient and teach emotional regulation strategies to ensure that the patient feels safe in treatment.

- Assessment: first we establish the memory we will be working on, then we identify the most disturbing image, the associated negative beliefs (“I’m not worthy”, “I’m in danger”) and physical sensations that accompany it.

- Desensitization: We use bilateral ocular movements, tapping or alternating sounds, and the patient observes how the memory changes and the emotional weight of it decreases.

- Installation: We reinforce an alternative positive belief, such as “yes I can” or “now I am safe”.

- Body scan: We check that the memory no longer activates a physical pain or discomfort

- Closure: We finish the session assuring that the patient is left feeling stable and calm

- Reevaluation: In the following session, we review the advances made and continue the process.

What does the patient experience?

People are often surprised at the speed with which the emotional intensity of the memory diminishes. Many describe the feeling of seeing the situation “from the outside” or realize the memory belongs in the past and no longer has power in the present.

Duration and frequency

The number of sessions depends on the complexity of each person’s history. Some people will experience relief in a few sessions, while others require more in depth work. This is best determined through a personal session with a therapist.

Benefits of EMDR Therapy

- Proven efficacy in the treatment of trauma, anxiety, and phobias

- Faster results than other therapy approaches in many cases.

- Respect for the patient: it isn’t necessary to go into detail about the trauma, which makes it easier to work on very painful experiences.

- Greater sense of control: the patient feels that they advance through milestones which causes the process itself to be motivating.

- Transcultural application: in my practice, I’ve successfully worked with people from different countries, ideologies, and cultural contexts.

One of the aspects that I most value of EMDR is that it turns the patient and the therapist into a team. Together we move toward freedom from the trauma, step by step, with the clear structure laid out by this approach.

EMDR Therapy in Madrid: how to choose a therapist

With the growing popularity of EMDR, more and more professionals have started offering the treatment. However, not all have the necessary training and supervision.

What to look for in an EMDR therapist

- Accredited training by EMDR Europe

- Supervised clinical experience in trauma

- More than 20 hours of supervisión, at a mínimum, with accredited experts in EMDR

- A safe and human approach, where the person feels accompanied

It’s never too late to change

Trauma does not have to be a life sentence. With EMDR, it is possible to free yourself from your past and regain trust in yourself. I’ve seen people overcome difficulties that they’ve faced for years, rediscovering their own strength and once again looking to the future with happiness.

If you are in Madrid and you feel that there are past experiences that are continuing to affect your present, EMDR may be the path for you.

About the author

Héctor Pastor Pardo is a general health psychologist specializing in addictions and individual and couples therapy. Trained in third-generation therapies and in psychopharmacology and drugs of abuse, he applies a cognitive-behavioral and integrative approach. He has completed the Standard Training of the Spanish Institute of EMDR (Level I and II). His primary practice is the treatment of adults and couples.

Division of Psychology, Psychotherapy and Coaching

Psychologist

Adults and couples

Languages: English and Spanish

The most common cognitive distortions in depression

Have you ever wondered what the mindset of a person with depression is like? Or perhaps you want to learn more about this disorder and its specific characteristics. One of the most studied and addressed aspects of cognitive behavioral therapy for depression is cognitive distortions. The goal of this article is to help you understand how cognitive distortions play a fundamental role in depressive disorders, including examples of how to identify and change them.

First, let’s better understand what cognitive distortions and depression are. The American Psychological Association (APA) defines cognitive distortions as «an erroneous or inaccurate pattern of thinking that contributes to the maintenance of negative emotions and dysfunctional behaviors. They are often automatic, rigid, and unconscious, and tend to reinforce dysfunctional beliefs about oneself, the world, and the future.» Some cognitive distortions include polarized (all-or-nothing) thinking, overgeneralization, emotional reasoning, or personalization, among others.

We can define depression as “A mood disorder characterized by persistent feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and loss of interest or pleasure in almost all activities. It may be accompanied by cognitive, physical, and behavioral symptoms, such as fatigue, difficulty concentrating, changes in appetite and sleep, and thoughts of worthlessness or excessive guilt.» Also, according to the APA.

Although depression is a specific disorder in the DSM-5, it is important to note that cognitive distortions can also occur in other types of disorders, such as anxiety or addictions. They can also be present even if the person does not meet the clinical criteria for any disorder. In other words, cognitive distortions can be observed in most psychological disorders and problems.

Cognitive Distortions in Depression

In individuals with depressive symptoms, these errors in thinking commonly occur systematically, affecting the perception and interpretation of situations about oneself, others, or the world. Cognitive distortions are learned, reinforced and, in some cases, can become part of the person’s personality structures and schemas. Cognitive distortions, as well as many other symptoms such as anxiety, are especially activated during times of stress or emotional vulnerability.

Detecting and changing our cognitive distortions is one of the best ways to contribute to our mental health. Which is why we will now explore options of practical ways and examples of how to do this.

In clinical practice, it is essential to identify and understand these thought patterns and the functions they serve in terms of thought, emotion, and behavior. In many cases, cognitive distortions do not occur solely as a result of a depressive episode, but act as predisposing and maintaining factors, causing the onset of these states. Ultimately, people with depressive symptoms have attentional distortions toward negative stimuli, as well as a negative interpretation of situations and themselves, which leads to the maintenance and reinforcement of symptoms. Therefore, during clinical intervention, it is necessary to confront and challenge these ways of acting and proceeding in patients and provide them with tools to deal with situations in a more adaptive manner. Let’s look at some examples.

Clinical examples of interventions to challenge cognitive distortions

Therapist’s goals: to foster in the individual the attitude of a detective of their own thoughts. First, to detect thoughts, without the desire to eliminate or fight them, but to accept them as the brain’s propositions. Second, to rethink the situation from a more rational and objective perspective.

1. Polarized Thinking (All or Nothing)

Case: Maria, 33, presents a project in her department. The project was delivered without incident and normally, and Maria says, «It was a complete disaster. If everything doesn’t go well, it’s useless.»

Possible questions:

a) Is there a more intermediate way of thinking?

Objective: To develop cognitive flexibility and realize that her performance is not as «black and white» as she initially thinks.

2. Emotional Reasoning

Case: Tom, 29, reports: “I feel like I can’t do anything right, so it must be true.”

Possible questions:

a) Do you think feeling this way means that you are that way?

b) What would someone who loves you say?

Objective: The validity of taking emotions as objective evidence of reality is questioned.

3. Arbitrary Inference

Case: Jaime, 27, reports that his partner is distant and concludes: «It’s clear she doesn’t love me anymore; I’ve lost her.»

Possible questions:

a) Could there be another possible explanation?

b) What is my basis for thinking this way?

c) What would another person in my situation tell me?

d) Would everyone think the same?

Objective: Begin to explore alternative hypotheses and loosen your initial certainty.

4. Minimization

Case: Toni, 28, always responds to praise for his work with something like, «It’s not that big a deal, this is normal.»

Possible questions:

a) Why is my work less valuable?

Objective: To challenge his tendency to minimize his achievements.

5. Overgeneralization

Case: Ana, 30, after a job interview that didn’t go well, comments: «I’m never going to get a good job.»

Possible questions:

a) I’ve made this mistake. Does that mean I’m a failure and worthless?

b) Does this apply to everything or to this specific event?

c) Watch your language and be wary of anything that makes general judgments about reality.

Objective: By limiting the scope of your thoughts, you reduce the associated emotional charge and minimize generalization.

6. Personalization

Case: David, 50, reports: “My daughter is very depressed, I’m sure it’s because I asked her to do her homework.”

Possible questions:

a) What other variables beyond my control can explain this situation?

b) Why am I relating this to myself?

c) Could it be due to other reasons?

Objective: To promote a more global perspective and better understand the emotional context in her environment.

7. Impositions or Rigid Rules

Case: Bob, 40, is frustrated because his friend canceled a plan at the last minute and explains, “He should have come on time; he always does the same thing.”

Possible Questions:

a) Is it realistic to ask others to always behave according to my wishes?

b) Was this done with malicious intent?

c) Is your friend capable of handling this differently?

Objective: To empathize, be flexible, and question rigid internal rules.

8. Selective Abstraction / Negative Filtering

Case: Bill, 26, received a critique amidst much praise while presenting his master’s thesis. Looking back, he says, «It was a horrible day.»

Possible questions:

a) Am I missing out on some of the information about the situation?

b) Am I only focusing on the negative?

Identifying our cognitive distortions doesn’t mean thinking “I’m wrong,” but rather starting to observe our thoughts with more curiosity and less harshness. Change doesn’t happen instantly, but recognizing these patterns is already an important step. Learning to question them, to see them in a more nuanced way, or simply not letting them take control of our actions is part of the path toward living more freely and with greater self-kindness. That’s why understanding how cognitive distortions shape depression allows us to intervene more effectively. Therapeutic progress often happens when people begin to rebuild a more realistic, compassionate, and flexible relationship with their thoughts.

About the author

Héctor Pastor Pardo is a general health psychologist specializing in addictions and individual and couples therapy. Trained in third-generation therapies and in psychopharmacology and drugs of abuse, he applies a cognitive-behavioral and integrative approach. His primary practice is the treatment of adults and couples.

Division of Psychology, Psychotherapy and Coaching

Psychologist

Adults and couples

Languages: English and Spanish

How do addictions work in the brain?

The first thing we have to understand is that the addictive substance or behavior in question and its use begins to be experienced as a basic need such as drinking water, eating or sleeping for the person suffering from the addiction.

As it is perceived as a basic need, people with addictive problems turn to the substance or behavior again and again despite the fact that it causes negative consequences in their lives. This is due to the fact that stopping consumption is experienced like stopping breathing for them at a neurobiological level.

Dopaminergic hypothesis of addictions

The scientific community agrees that the dopaminergic hypothesis of addictions is the explanation with the most evidence regarding why people develop addictive disorders. An addictive disorder implies a dysregulation of the brain’s reward circuit.

The reward circuit

The reward circuit, also known as the pleasure circuit, is responsible for facilitating our survival. This system is where dopamine processing occurs in the brain. Dopamine is the pleasure hormone and thanks to it and the reward circuit we can experience, feel and interpret pleasure. The reward circuit is a series of connections between different areas of the brain, mainly the prefrontal cortex and the reptilian brain.

The reptilian brain is a set of areas such as the ventral tegmental area or the nucleus accumbens, and it is responsible for emotional memory and the survival instinct. It is a more primitive area of the brain and has not changed much throughout human history, especially when compared to the prefrontal cortex. Our reptilian brain today is very similar to that of other animals.

The prefrontal cortex is the most modern area of the brain, as it has evolved the most in human history. If we compare a brain of homo sapiens and that of a modern human, the greatest differences would be found in the larger size and connectivity of the prefrontal cortex. The prefrontal cortex is in charge of higher level thinking, decision-making, processes related to motivation and achievement of goals, discerning between good and evil, etc. In short, it is of great importance in terms of the direction and execution of behaviors.

To fully understand addictions in the brain, we must know that the reward circuit aims to guarantee our survival and uses the secretion of dopamine to reinforce behaviors so that they are repeated. All behaviors that are linked to our survival secrete dopamine, for example, drinking water, eating, raising children, etc. This helps them to be experienced as something pleasant and repeated in the future.

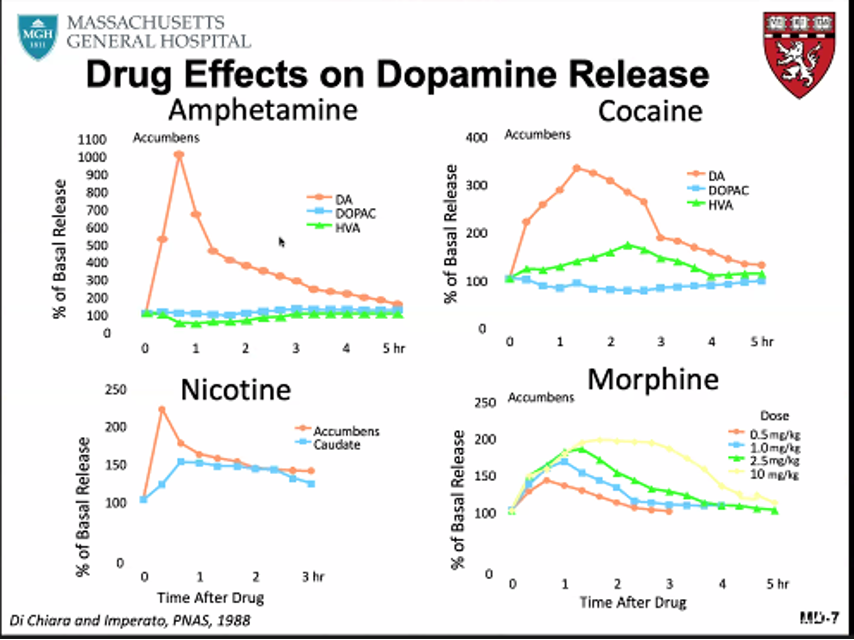

There are a series of behaviors that arise in a more recent part of human history such as drinking alcohol, getting drunk, consuming drugs by different means of consumption (oral, smoked, snorted, injected) or gambling. At the dopaminergic level, these behaviors present a great challenge to our reward system, since in nature we do not find anything that is as reinforcing at the level of dopamine as these behaviors.

There is an exponential difference in dopamine levels between the behaviors that are typically abused (drugs, gambling) compared to other behaviors in our daily lives.

We can see how cocaine consumption leads to dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens of more than 250% above the base level, while other pleasurable behaviors such as sex or eating would increase it between 100% and 50% above the base level respectively. Although different substances generate different spikes in dopamine, drugs or gambling are characterized by generating levels of dopamine that are not found in the person’s natural environment and, therefore, are more capable of generating addiction than other behaviors or substances in nature. However, any behavior that generates dopamine would have the potential to become addictive, which is why you can find cases of addictive problems with food, sports, social networks, sex, video games or the internet, among many others. The person’s relationship with such behaviors becomes toxic and begins to have different consequences in the person’s life.

Upregulation of dopaminergic neurotransmitters

When the abuse of a certain substance or behavior becomes habitual enough, the dopaminergic neurons of the reward circuit will undergo an upregulation of their dopaminergic transmitters due to the high amount of dopamine they are now regularly working with. It can be said that when the dopaminergic neurons of the reward circuit upregulate their neurotransmitters, a person has the disease of addiction. This upregulation will be a determinant in an addictive problem being maintained over time and in the inability to stop consuming as it is the main cause of craving. Craving describes a brief and intense period of time in which a person feels an urge to consume, accompanied by thoughts about consumption, as well as other psychological and physiological reactions.

Abstinence: When you stop using...

When a person stops using, the upregulation of neurotransmitters is reversed, which leads to the spacing out of the craving episodes over time while they reduce their intensity. This process could last from a few months to years after quitting consumption and, in any case, a relapse could reactivate the entire reward system back to the levels that existed during active addiction. This is possible thanks to brain neuroplasticity: the ability of our brain to change the way it connects areas to each other.

Awareness of the disease for those who suffer from addiction problems is essential to stay in recovery. Consumption or execution of the addictive behavior will cause the reward system to stimulate the connections previously established during active addiction and in turn reactivate all of the person’s old attitudes and defensive mechanisms associated with their addiction. It will be essential for the person to take advantage of this stage to generate new strategies for managing their emotions, work on their beliefs about life, about themselves and the world, as well as hobbies that help them fill the time and emptiness caused by abandoning addictive behavior.

The Reptilian Brain Hijacking the Prefrontal Cortex

The prefrontal cortex tries to regulate addictive behavior through attempts to control or stop consumption, but when the reptilian brain, specifically the nucleus accumbens, requires large amounts of dopamine, it will hijack the prefrontal cortex and, consequently, the ability to make rational decisions. When the reptilian brain craves dopamine, it dictates a person’s behavior. It is important that we understand that addictions cause dysregulation of the brain which leads to emotion dysregulation. Planning and executing the behavior leads to dopamine segregation, the person also perceives that these actions lead to pleasant sensations and a better mood, which reinforces the behavior.

Of course, this does not make the person less capable or intelligent, simply someone who, in addition to the basic needs that we all know, perceives that they have another need due to the disease. In order to maintain consumption, it is essential that the disease produces protection mechanisms against other people or against the prefrontal cortex itself (which tries to regulate consumption). Mechanisms such as denial, minimization, lying, concealment and many others. Denial can provoke angry responses towards people who try to control the addict’s consumption. There are also many internal mechanisms to protect the addiction from the prefrontal cortex, such as control perception or downplaying the negative consequences.

Addicted people intend to stop consuming from their prefrontal cortex, but when the reptilian brain craves dopamine, it takes control of the behavior and activates mechanisms to continue consumption. Addiction is not chosen, therefore, no one should be blamed for it but assume responsibility and start taking actions to change. If you think you or someone else has these kinds of problems, seek help.

About the author

Héctor Pastor Pardo is a general health psychologist, specialist in addictions and individual and couples therapy. Trained in third-generation therapies and in psychopharmacology and drugs of abuse, he applies a cognitive-behavioral and integrative approach. Its main activity is in the treatment of adults and couples.

Division of Psychology, Psychotherapy and Coaching

Psychologist

Adults and couples

Languages: English and Spanish

How do I know if I have a problem with alcohol?

If you’ve ever asked yourself what’s the line that separates low risk alcohol use and an alcohol addiction, this article is for you.

Problematic alcohol use presents itself in different forms in our society. It can be defined by a combination of different criteria leading to people with very diverse consumption habits, but all with one common problem: difficulties controlling their consumption leading to negative consequences in their lives. Additionally, there are varying degrees of severity amongst alcohol problems, but all share the loss of personal liberty in favor of alcohol.

It is estimated that around 5% of Spain’s population could have an alcohol problem. Therefore, it is crucial to increase awareness of this disorder, so it is easier to detect and intervene early.

Any diagnosis should be conducted by a mental health professional. If you identify with the following points, seek help from a professional specialized in addictions.

Signs that show you might have an alcohol problem

You could have problems with alcohol if you meet 2 or more of the following criteria during a period of 12 consecutive months:

1. Alcohol is often consumed in larger amounts or over a longer period than was intended.

This criterion refers to the inability to control the conduct of drinking or the amount you drink during a year. If you find yourself drinking on more occasions or in larger amounts than you planned, this may indicate that you have an alcohol problem. Some people with this issue try to minimize the importance of the consequences of their consumption, hide their drinking from others, or use a variety of masking techniques such as only acknowledging some of their drinking. It is also common to lie to yourself about the reality of your drinking and subsequent consequences as a defense mechanism.

2. There is a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control alcohol use.

Attempts to reduce or stop drinking can stem from promises to family and friends or even promises with oneself to stop drinking after experiencing a bad hangover. After multiple failed attempts to gain control over drinking, it’s typical for an alcoholic to normalize and adapt their life around their drinking.

Difficulty with stopping alcohol consumption is caused by withdrawal symptoms and craving. Withdrawal symptoms can be physical in extreme cases (tremors, sweating, etc.) or psychological (irritability, cravings, apathy, etc.). When the brain adapts to habitual drinking, it becomes accustomed to high levels of pleasure in the form of dopamine (the pleasure hormone), so the brain sends signals of needing to drink in the form of withdrawal symptoms when it feels the need for dopamine. Additionally, alcohol use can become an established coping method when facing difficult situations or emotions.

For these reasons, the brain triggers the appearance of withdrawal symptoms such as irritability, sadness, and apathy when a person isn’t drinking as well as the appearance of consumption thoughts associated with these emotions resulting in relapse. Withdrawal has an important neurobiological basis; the more emotional and primitive part of the brain (called the reptilian brain) hijacks the more rational side (called the neocortex) to keep drinking.

3. A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain alcohol, use alcohol, or recover from its effects.

This criterion accounts for both the amount of time spent drinking alcohol as well as the amount of time spent recovering from the subsequent effects such as sleeping, resting, or feeling unproductive due to a hangover (preventing one from doing house chores or self-care, for example). The experience of unpleasant emotions due to a lack of control in your alcohol consumption can typically lead to a desire to quit drinking, but a person can have difficulty maintaining that motivation once the withdrawal symptoms appear.

When one’s drinking is very recurrent, it could lead the person to begin isolating themselves from their environment and start spending more time drinking at home, at bars, with drinking buddies, etc, but they could also use socializing to camouflage their drinking as just a social act.

This becomes a habit in their life, although it’s not necessary to drink every day, blackout, or drink until you vomit to have a problem with alcohol. In fact, many people present problematic drinking patterns that aren’t daily, such as weekend drinkers.

4. Craving, or a strong desire or urge to use alcohol.

They are characterized by brief periods of time in which someone experiences anxiety accompanied by a desire to drink. This can last anywhere from seconds to hours and appears alongside other emotions. For example, a person can feel a craving accompanied by anger due to not being able to drink or feel pleasure. Or a craving could be accompanied by feelings of sadness or guilt due to being unable to successfully control their drinking. It is common that the development of an alcohol problem includes drinking associated with cravings. Craving can still happen even months after stopping drinking.

5. Recurrent alcohol use resulting in a failure to fulfill rote obligations at work, school, or home.

These problems can range anywhere from extreme negligence to small errors. Some examples could include going to work late, missing classes, arriving late, not following through on commitments, or avoiding phone calls. Additionally, habits like neglecting family or personal hygiene and diet.

6. Continued alcohol use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the effects of alcohol.

It’s common that people who have alcohol problems have had it brought to their attention by their family, partner, or friends. After which can unfold a series of conversations or promises to control their drinking that continue for months or years until the people close to them pull away. It is very difficult for friends and family to put themselves between the drinker and their habit. The motivation to stop drinking must come from the person with the drinking problem in order for them to successfully make a change, which can be very frustrating to family or friends.

7. Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of alcohol use.

When the habit of drinking starts to expand in a person’s life, they begin to substitute other activities for drinking. It’s common to change plans on the weekend to instead spend most of their time on alcohol related activities or change after work habits to favor drinking. When someone manages to quit drinking, finding other recreational activities to occupy the time previously spent drinking can be quite a challenge. On a neurobiological level, it is complicated to adjust to new activities due to a lower stimulation in the brain’s reward center compared to the one produced by drinking.

8. Recurrent alcohol use in situations in which it is physically hazardous.

Alcohol consumption commonly can produce disinhibition of conduct thanks to a lowered perception of risk. Due to this people take more risks than usual under the influence of alcohol. When a drinking habit is very established, many risky behaviors become normalized such as driving home while under the influence of alcohol, operating machinery, or going to work hungover.

9. Alcohol use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by alcohol.

Due to the negative reinforcement that is produced by addiction, it is common to turn to drinking to stop feeling unpleasant emotions such as guilt, sadness, doubts, fear, or anxiety amongst others. This reinforces drinking behaviors which in turn worsens the behaviors. Emotional difficulties in people’s lives that alcohol provokes can be minimized since alcohol can also help the drinker manage their emotions since it takes away the craving, thus perpetuating the problem.

10. Tolerance, as defined by either of the following:

- A need for markedly increased amounts of alcohol to achieve intoxication or desired effect

- A markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount of alcohol.

Tolerance acquired from alcohol can cause an amount that once seemed like a lot to change over time to seem like very little. Tolerance is due to the increased regulation of dopamine receptors in the brain’s reward system among many other adaptive factors of the metabolization of alcohol that occurs in the body.

11. Withdrawal symptoms when the effects of alcohol are not present.

Alcohol abuse can cause physical or psychological withdrawal symptoms such as trouble sleeping, tremors, restlessness, nausea, sweats, accelerated heart rate, convulsions, or seeing things that aren’t there. The presence of these symptoms usually indicates a person’s alcohol problem is considerably severe.

How many drinks indicate a risky level of consumption?

A consumption equivalent to 4 beers per day for men or 2-2.5 beers for women indicated risky alcohol consumption.

You can calculate the sum by taking the average number of drinks consumed over the course of the week or month. Some days you may drink more than others, especially since it is common to binge drink when dealing with an alcohol problem. The term binge drinking defines a form of consumption in which someone drinks at a high velocity to obtain a greater effect, for example drinking quickly before doing any activity such as coming home after work, before going to work, before going into a night club, etc.

Additionally, people who meet the criteria for alcohol abuse usually present symptoms for other mental conditions such as anxiety or mood disorders. As far as personality traits, impulsivity and pleasure seeking are more prevalent in people in treatment for alcoholism.

The Ministry of Health, Consumption, and Wellness employs the Standard Drink Units to inform the population of the levels of risk associated with alcohol: “A Standard Drink Unit of alcohol, in Spain is the equivalent of 10 grams of alcohol which is, approximately, the amount of half a glass of wine at 100 ml at 13 percent, 1 300ml glass of beer at 4 percent, or 30 ml of liquor at 40 percent.” Nowadays, the following criteria are used to determine risky drinking levels:

1. Through the AUDIT questionnaire: > 7 points in men, > 5 in women

2. Consumptions of 40 percent per day (4 SDUs/day) in men and > 20-25 percent per day (2-2,5 SDUs/day) in women.

According to DSM-5, any person that meets 2 or more of the 11 criteria during the same period of 12 months would receive a diagnosis of disordered use of alcohol. The intensity- light, moderate, or intense- is based in the number of criteria which are present:

- Alcohol is often consumed in larger amounts or over a longer period than was intended.

- There is a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control alcohol use.

- A great deal of time is spent on activities necessary to obtain alcohol, use alcohol, or recover from its effects.

- Craving, or a strong desire or urge to use alcohol.

- Recurrent alcohol use resulting in a failure to fulfill rote obligations at work, school, or home.

- Continued alcohol use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the effects of alcohol.

- Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of alcohol use

- Recurrent alcohol use in situations in which it is physically hazardous.

- Alcohol use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by alcohol.

- Tolerance, as define by either of the following:

- A need for markedly increased amounts of alcohol to achieve intoxication or desired effect

- A markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount of alcohol.

- Withdrawal symptoms when the effects of alcohol are not present.

About the author:

Héctor Pastor Pardo is a General Health Psychologist with experience in addictions, individual therapy, and couples therapy. Trained in Third Generation Therapies with a focus in cognitive behavioral and integrative therapies. His main focus is the treatment of adults and couples.

Division of Psychology, Psychotherapy and Coaching

Psychologist

Adults and couples

Languages: English and Spanish